Welcome back to discovering another female artist from the past, with co-host Rebecca Budd, curator of Chasing Art!

Resa – So, Rebecca we travel back to the 1600’s Netherlands and find this amazing woman, Anna Maria van Schurman. Are you dizzy from our time travel globe trotting, and your research homework, yet?

Rebecca – Our journey back to the 1600s in the Netherlands was nothing short of extraordinary. Meeting Anna Maria Van Schurman, a remarkable figure of her time, left a lasting impression on me. Her intellect and artistry were truly inspiring, and I felt privileged to witness the world through her eyes. Resa, you orchestrated this incredible adventure, taking me on a whirlwind exploration of history and culture. I am deeply grateful for the memories created during this remarkable experience.

Resa – Aw, thank you Rebecca! Without further ado, here is Anna Maria van Schurman.

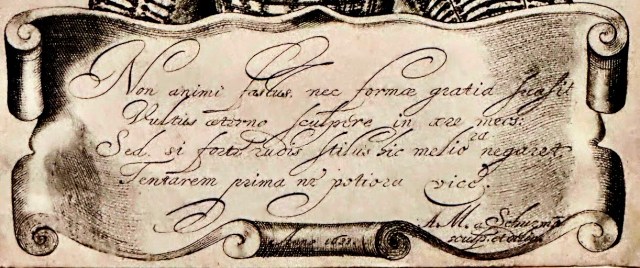

“No Pride or Beauty”

Anna Maria van Schurman (November 5, 1607 – May 4, 1678) was a remarkable figure in Dutch history, known for her diverse talents and her advocacy for female education. She was a painter, engraver, poet, classical scholar, philosopher, and feminist writer. She is best remembered for her exceptional learning and her defence of female education.

With outstanding proficiency in multiple disciplines, including art, music, and literature, Van Schurman’s remarkable intellect and dedication to learning set her apart. She left a lasting legacy as the first woman to unofficially study at a Dutch university.

No pride or beauty prompted me

to engrave my features in eternal copper;

But if my unpractised graver was not yet capable of producing good work,

I would not risk a more weighty task the first time.

Education and Achievements

Anna Maria van Schurman received a strong classical education from her father, establishing herself as a child prodigy. By the age of seven, she demonstrated exceptional proficiency in reading and translating Latin and Greek. Impressively, by age eleven, she had also acquired proficiency in German, French, Hebrew, English, Spanish, and Italian. Furthermore, she delved into the study of art, ultimately becoming a distinguished artist in the disciplines of drawing, painting, and etching, albeit with few surviving examples of her artwork.

Following her years of fervent advocacy for women’s education, van Schurman was finally extended an invitation to attend the University of Utrecht at the age of 29, marking a significant milestone as the first female student. However, her presence in the university was subject to the stipulation that she conceal herself behind a curtain during classes, a measure taken to prevent any potential distraction for her male counterparts. Despite these challenges, she graduated with a degree in law, consequently becoming the first female to achieve this educational feat.

A polyglot adept in fourteen languages, her linguistic abilities encompassed Latin, Ancient Greek, Biblical Hebrew, Arabic, Syriac, Aramaic, Ethiopic, as well as various contemporary European languages.

Van Schurman’s journey exemplifies her relentless pursuit of knowledge and her groundbreaking contributions to female education.

Professional engraver Magdalena van de Passe taught Anna the art of engraving.

In an 8 x 10 frame next to a 6 X 8 frame in the AGO, one can see how tiny the self portrait is.

Advocacy for Female Education and Intellectual Contributions

Anna Maria van Schurman’s unwavering commitment to advocating for female education and her active participation in intellectual discourse significantly contributed to the advancement of women’s rights and intellectual equality in the Dutch historical context.

One way Anna Maria van Schurman advocated for equal education for women, was through her prolific writings during the 1640s and 50s. In her notable work “Whether the Study of Letters is Fitting for a Christian Woman,” published in 1646, she passionately argued for the educational rights of women, upholding that individuals with aptitude and principles should have the opportunity to pursue learning. She ardently believed in the importance of women receiving comprehensive education across all subjects, provided that it did not impede their responsibilities within the domestic sphere.

Resa – Were you surprised to get an email, while working on this post, with a link to Anna van Schurman’s book The Learned Maid (1659)? I know I sure was.

Rebecca – It was indeed a surprise, Resa! I read that Anna van Schurman’s “The Learned Maid, or, Whether a Maid may be a Scholar” emerged from her extensive correspondence with theologians and scholars throughout Europe, focusing on the crucial topic of women’s education. She argues that educating women not only enriches their lives but also benefits society as a whole! I was astonished by Anna’s progressive stand in a time when women’s education was often discouraged. To state boldly that knowledge is not limited by gender was a courageous endeavour.

Notably, van Schurman actively engaged in the dissemination of articles elucidating the intellectual equality between men and women, countering the prevalent notion that women were solely suited for roles as wives and mothers. Her contributions to contemporary intellectual discourse were expansive, involving exchanges with influential cultural figures such as philosopher René Descartes, philosopher Marin Mersenne, and writer Constantin Huygens . These interactions further solidified her influential presence within the intellectual circles of her time.

Later Life and Involvement with Labadism

Toward the end of her life, Anna Maria van Schurman became involved in a contemplative religious sect founded by the Jesuit Jean de Labadie known as Labadism. This mystic offshoot of Catholicism preached the significance of communal property and included the directive to raise children communally. Van Schurman, deeply involved in the sect, became de Labadie’s primary assistant and journeyed with the sect as it traveled. Her association with de Labadie facilitated the publication of her final book “Eucleria,” in 1673, which is considered one of the most comprehensive explanations of Labadism.

Her engagement in Labadism at the later stage of her life showcased her continued pursuit of spiritual and intellectual endeavours, further enriching her diverse legacy.

Resa – I’d never heard of Labadism, until this article. Interestingly, Van Schurman refers to herself as “that incomparable Virgin” on the opening page of “The Learned Maid”. Do you find it odd that such a scholar would join up with a religious offshoot? It sounds like a cult.

Rebecca – That is a very good question, Resa! In her 60s, Anna van Schurman became a prominent figure among the Labadists, a religious group that emerged in the 17th century, characterized by their communal living and strict adherence to a mystical interpretation of Christianity.

While some critics labeled the Labadists as a cult due to their unconventional beliefs and practices, including their rejection of mainstream religious authority and emphasis on personal revelation, supporters viewed them as a genuine spiritual community seeking to live out their faith in a more profound way. The debate over their classification often hinges on the definitions of cult versus legitimate religious movement, reflecting broader societal attitudes towards alternative spiritual paths.

Resa – Rebecca, thank you, thank you for joining me in this series on self-portraits from the MHM exhibition!

Rebecca – This has been a marvellous series, Resa. Your innovative approach entices us all to enter the“rabbit hole”of creativity. When we go back to honour artists, we give honour to our time. And when we give honour to the “now”, we become more creative and give our voice to the future.

Click on the above banner to see Rebecca’s research links!

You can also listen to Rebecca and her guest on her podcasts!

Photos taken by © Resa – May 14, 2024

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada

You must be logged in to post a comment.