They were not royalty, but may have painted for royalty.

Their parents worked for royalty, were politicians, acclaimed artists or important clergy. These aristocrats wielded economic, political, and social influence. They were fortunate ones, before and during the rise of a European middle class due to the industrial revolution.

Louise-Adéone Drölling

French – 1797 – 1831

Louise-Adéone‘s father, Martin Drölling, and older brother, Michel Martin Drölling, were celebrated artists in their day. At the age of 15 she was encouraged to begin painting.

In 1819, Louise-Adéone married architect Jean-Nicolas Pagnierre. Widowed in 1822, she remarried Nicholas Roch Joubert in 1826. Joubert, chief tax officer of Paris, was the son of politician and former bishop Pierre-Mathieu Joubert. They had two daughters, Adéone Louise Sophie, and Angélique Marie.

Louise-Adéone Drölling, aka Madame Joubert won a Gold Medal from Salon des Amis des Arts, for her above painting; Young Woman Tracing a Flower. Thought be a self portrait, it later became part of the distinguished collection in the Gallery of La Duchesse de Berry.

I have found conflicting dates of her Gold Award – 1824, 1827 or 1831.

Marguerite Gérard

French – 1761 – 1837

Marguerite Gérard attained much wealth and real estate during her life, despite remaining unmarried.

In 1775 she moved from Grasse to Paris and lived with her sister’s family. Her sister was married to the popular Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Here she had financial freedom and was trained in art as Fragonard’s unofficial apprentice.

By her mid 20’s, Gérard had achieved a signature style. This involved precise details made with subtle and blended brush strokes, inspired by 17th-century Dutch genre paintings. However, she made it her own by focusing on females in intimate domestic settings.

In the 1790’s, once the Salons were opened to women, she exhibited often, winning three medals.

Over the course of her successful fifty years, Gérard survived the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars.

Her paintings were acquired by luminaries such as Napoleon and King Louis XVII.

Her small-scale, portable canvases appealed to many wealthy collectors, who preferred to display her small scale still life and genre paintings in their homes, over large historical canvases.

The numerous engraved versions of Gérard’s paintings made them accessible to less affluent art lovers and helped increase her reputation.

Gérard did not always follow convention, turning down a place at the French Royal Academy.

Catherine Lusurier

French – 1753 – 1781

Catherine Lusurier died at the young age of 28 years old. There is not a lot known about her, and only a few known signed paintings are accounted for.

Her mother, Jeanne Callot, was a dressmaker, while her father Pierre was a milliner. Apprenticing under her uncle, Hubert Drouais (1699-1767), her work bears his stylistic influence. Her paintings are predominantly portraits of children and artists.

A Catherine Lusurier work recently headlined Christie’s Old Masters and 19th Century Paintings, selling from a Private Collection. Sold Without Reserve at 3.11 million dollars, it exceeded the pre-sale high estimate.

Amélie Legrand de Saint-Aubin

French – 1797 – 1878

Amélie Legrand de Saint-Aubin, the eldest daughter of Pierre Jean Hilaire Legrand de Saint-Aubin (1772–1839) and Denise Marie Claudine Legrand (1772–1855), was born in Paris. After training and studying in the Women Only Studio with Charles Meynier, Amélie Legrand de Saint-Aubin‘s Rococo style portraits and history paintings grew in popularity.

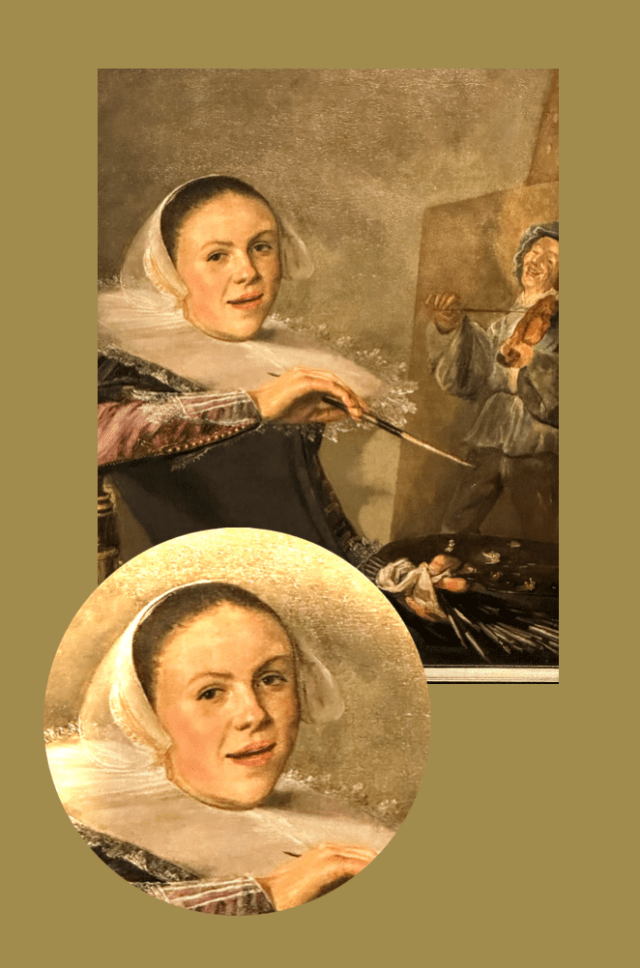

Portrait of an Artist Drawing a Landscape in her Sketchbook is of a long standing tradition of women artists picturing women painting art.

Political changes from the French Revolution resulted in women being allowed to exhibit in the French Salon. Amélie Legrand de Saint-Aubin went on to exhibit at 17 salons over the course of her career.

Around 1831, she began teaching, offering private lessons. She never married.

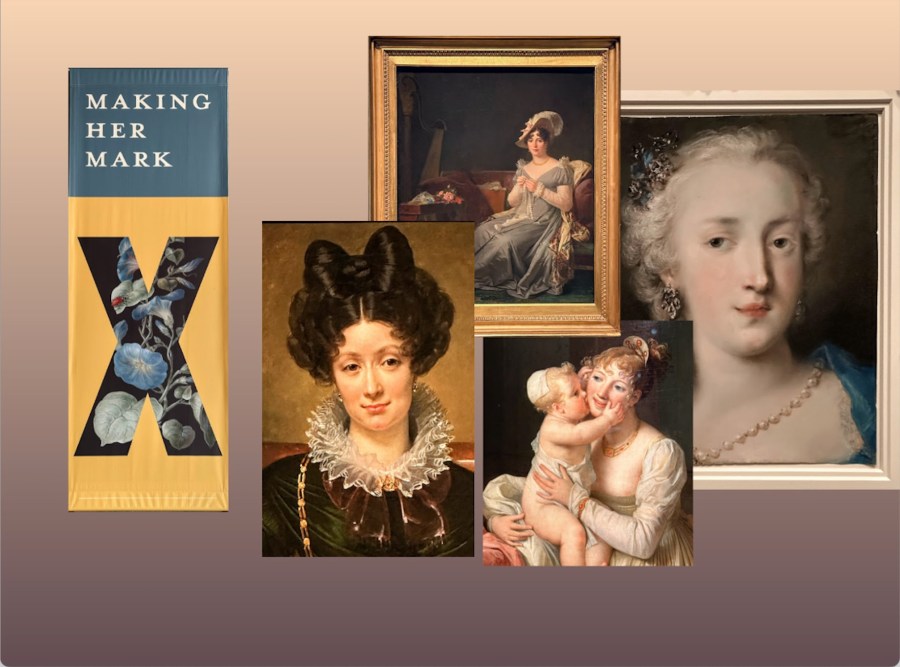

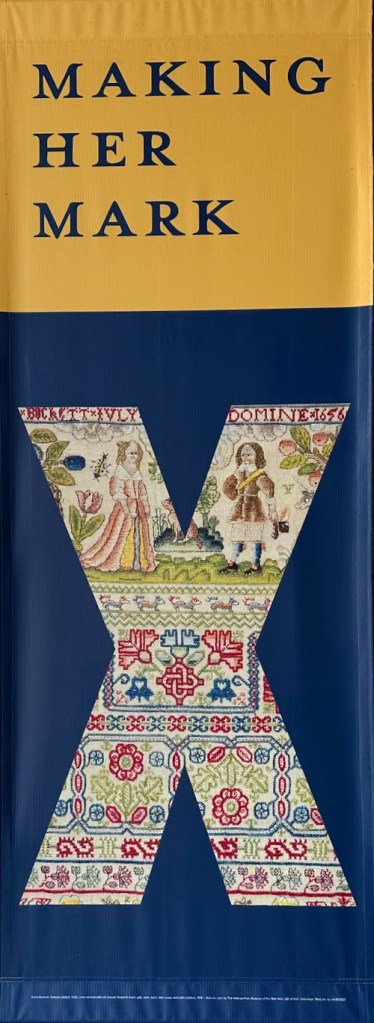

“This stunning portrait recently joined the AGO’s permanent collection and made its debut as part of the exhibition Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe 1400 – 1800. “

Marie-Guillemine Benoist

French – 1768 – 1826

Marie-Guillemine was born in Paris. Her mother was Marguerite-Marie Lombard and her father, René Laville-Leroux, a royal administrator for the ancien régime state. Marie and her sister, Baroness Larrey, (1770–1842), studied art from Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun. Later they studied under Jacques-Louis David.

Her first exhibition was in 1784, at an annual 1 day show in Paris – Exposition de la Jeunesse.

Until the Louvre Salon became open to all exhibitors in 1791, where Benoist was one of 22 women presenting, she showed yearly at the Exposition de la Jeunesse.

At the Salon in 1804, she won a medal, whereby France’s new Emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte, ordered multiple commissions.

Other than her Salon successes, which are in the French state collection, Benoist’s work, including Portrait of a Lady was attributed to a man; in her case, Jacques Louis David.

Like many women artists of her day, their posthumous fate was to be overlooked, forgotten and/or effaced.

Mary Beale

English – 1633 – 1699

Mary Beale was the daughter of a clergyman, John Cradock, so it seems natural that much of her portraiture is of churchmen. It is not sure who she trained under, but she received considerable guidance from Peter Lely

In London, she moved in intellectual circles. By, and into the 1670s she was in demand as a portrait artist, earning enough money to support her family of four.

After several years of mundane civil service; Mary’s husband, Charles Beale, left his monotonous job to become her full time studio manager.

Much has been learned from the many notebooks he kept.

One example: Charles recorded that in 1677 Mary completed 90 commissioned portraits. There were 31 female sitters and 34 male. The women and girls were mostly either titled or gentry. Men and boys were gentry or of “middling sort.”

Rosalda Carriera

Italian – 1673 – 1757

Rosalba Carriera was born in Venice to Andrea Carriera, a lawyer, and lacemaker, Alba Foresti. Taught to make lace by her mother, little is known of her artistic training. She is renowned for pastel portraiture and allegories.

In 1720, during a stay with French banker Pierre Crozat in Paris, Rosalba created portraits of Louis XV as a child, and members of the French aristocracy. Here she developed a friendship with Antoine Watteau, who influenced her work.

Rosalba is one of the originators of the Rococo style in Italy and France.

Her greatest patron, Augustus III of Poland, collected more than 150 of her pastels. He also sat for her in 1713.

In 1746 she lost her sight, but her work continued to influence many other artists.

I’ve merely highlighted these women’s lives. There is so much more to know about our trailblazing sisters, who went before us.

Click on Making her Mark above to view sources.

All photos taken by © Resa McConaghy – May 14, 2024

Making Her Mark exhibition – Art Gallery of Ontario

You must be logged in to post a comment.